By Navras J. Aafreedi

All translations from Urdu by Saira Mujtaba

Kuchh suni-ansuni dāstānoṅ méiṅ jo tumné dekhā-sunā sabsé main hūṅ judā

Mujhko dékho to dékho nayé rang méiṅ, be-irādā mohabbat kā andāz hūṅ!

Amongst tales, those known and unheard, whatever you’ve seen-heard; I’m different from them,

If you choose to look at me, then see me with a different hue – I’m a way of selfless love!

The poet who wrote this couplet spent half his life, the second half, with me, while I spent almost all my life with him until I moved out a decade ago. Although he was my father and I, his only child, he insisted that I do not use any of the forms of address generally used for a father. Instead he preferred that I call him An’nā. Not that he was Tamil and that he wanted to be seen as my elder brother, what the Tamil word an’nā means, but because he saw An’nā as an abbreviation of his pseudonym Anwar Nadeem. This desire of his, as many of his other desires, emanated from his discomfort with norms and conventions, which he expressed in his nazm (a genré of Urdu poetry) “Hamāré Qātil” (Our Murderers):

Maut kī nīnd sé pahlé bhī inhéiṅ dékhā thā

Ākhirī bār yahī log milé thé ham sé

Apnī tārīk-mizājī ko sajāyé rukh par

Apnī uljhan ko lapété hué apné sar par

Ungliyāṅ zulm kī, tasbīh ké dāné majbūr

Bhoṅdé māthé pé sajāyé hué chāval kī lakīr

Khud uṛāté hué kuchh zauq-é-salībī kā mazāq

Pīli chādar méin lapété hué kālī rūhéiṅ

Apné hotoṅ pé sapédī ko lapété chahré

Maut ki nīnd sé pahlé bhī inhaiṅ dékhā thā

Ākhirī bār yahī log milé thé ham sé

Hamné phūloṅ kī haṅsī, chānd ki kirnéiṅ lékar

Jī méiṅ thānī thī basāyéiṅgé mahbbat kā jahāṅ

Bas yahī log tabhī āyé thé yé kahné hamsé

Zindagī rasm ké sansār méiṅ ābād karo

Rūh ké pānv méiṅ zanjīr-é-ibādat dālo

Kohnā afkār kī chādar ko lapéto sar sé

Aur sajdé méiṅ jhukāo yé mahabbat kī zabīṅ

Maut kī nīnd sé pahlé bhī inhaiṅ dekhā thā

Ākhirī bār yahī log milé thé hamsé

In kī bātoṅ pé hansé, hans ké yahī hamné kahā

Ham nahīṅ zauq-é-ibādat se pighalné vālé

Ham nahīṅ apné irādoṅ ko badalné vālé

Apné kānoṅ méiṅ faqat dil kī sadā ātī hai

Ham kahāṅ dahar kī āvāz sunā karté hain

Ham ko kyoṅ rasm ké sansār méiṅ lé jāogé

Ham ko kyoṅ kohnā ravāyāt sé taṛpāogé

Ham haiṅ āvārā-mizājī ké payambar, yāro!

Ham se gar sīkh sako, sīkh lo jīnā, yāro!

Maut kī nīnd sé pahlé bhī inhaiṅ dekhā thā

Ākhiri bār yahī log milé thé hamsé

I’d seen them before the eternal sleep of death,

These very people had met us at the final hour,

Decorating their historical pride on their faces,

Twining their worries on their heads,

Cruel fingers, helpless lie the rosary beads,

Embellishing a vermillion line of rice on their crude forehead,

Enveloping black souls with a yellow mantle,

Faces, donning a paleness on their lips,

I’d seen them before the eternal sleep of death,

These very people had met us at the final hour.

We had gathered the smiles of flowers with moonbeams,

And had pledged to inhabit a world full of love,

It was then when these people came to tell us,

Live life as per the wordly rituals,

Chain thy soul with the shackles of prayers,

Wrap thine head with the age-old worries,

And bow in prostration, thy brow of love.

I’d seen them before the eternal sleep of death,

These very people had met us at the final hour.

We retorted with a smile and said,

We aren’t going to melt with the taste of prayers,

We aren’t going to alter our beliefs,

Our ears pay heed to only the voice of the heart,

Why would you take us to the world of rituals?

Why would you flutter us with age-old worries?

We are the messengers of free-spiritedness.

I’d seen them before the eternal sleep of death,

These very people had met us at the final hour.

He wrote, but only seldom submited his writings to journals for publication. He published books, both of prose and poetry, but never bothered to market them. He aspired to be a film actor, but never went to Bombay (now Mumbai) to try his luck in the Hindi/Urdu film industry there. He respected those who toiled to make a living and was also full of self-respect, but did not shy from being dependant on his wife for his subsistence. He inherited wealth, but did not cease to be a spendthrift to share the household expenses with his wife, who singularly took care of all household responsibilities. He was at once a thinker and a poet, but preferred the company of simple folk. There seemed to be little compatibility between him and his wife, yet he stayed in marriage with her for decades until his death. He was an enigma.

He was an eternal outsider, incapable of being an insider, uncomfortable being member of any group entity, indifferent to social expectations, and strongly independent, as expressed in his nazm “Asīr-é-Jamā’at”:

Ae méré dosto!

Ae méré sāthiyo!

Tum isī ahad ké

Meiṅ isī daur kā

Zindagi kā alam

Ātmā ki khuśī

Tīragī kā sitam

Rauśnī kī kamī

Gham tumhārā, méré dil kā méhmān hai

Mérā gham hai tumharé diloṅ méin makīṅ

Zindagi ko magar dékhné ké liyé

Sochné ké liyé, nāpné ké liyé

Zindagi ko baratné kī khātir magar

Zāviyā bhī alag

Fāsla bhī alag

Hauslā bhī alag

Tum uthāyé ravāyat kī bhārī salīb

Tum baghal méiṅ dabāyé purānī kitāb

Tum jo lafzoṅ ké darpan ko chhū lo agar

Chhūt jāyé vahīṅ dast-é-tāsīr sé

Tum purāné zamānoṅ sé mānūs ho

Tum ki bujhté charāġhoṅ kī taqdīr ho

Tum asīr-é-jamā’at, méré sāthiyo!

Tum kahāṅ fardiyat ko karogé qabūl

My friends!

My Comrades!

You’re of this age,

I’m too of this epoch,

The flag of Life

The bliss of the soul

The gloom of tyranny

The void of light,

Your sorrow is my heart’s guest

My sorrow resides in your heart

But in order to witness Life

To ponder over it, to measure it,

To make use of this life,

Having a different angle,

A different distance,

A different spirit.

You carry the heavy cross of traditions,

You thrust an archaic book under your arms,

If only you touch the mirror of words

Your hands would let go off their impressions.

You’re stuck to the eras gone by,

For you’re the fate of flickering lamps,

You’re chained to a herd mentality, my comrades!

Why would you approbate individuality?

At the same time, he was extremely generous to the poor and brutally honest. When he built our modest dwelling, he got the name of each labourer who worked during its construction inscribed in golden letters on a black granite stone expressing our gratitude to them. He called them ‘mahnatkash fariśté’ (hardworking angels). He extended those labourers the same hospitality as he did to any friend who visited him at the construction site while he supervised the work. Even when any of those labourers visited us at our house long after its construction, he would be welcomed as any esteemed guest would be, quite unusual in a society where the dignity of labor is not deeply embedded. He had a privileged life: he did not have to work for a living as he had inherited some wealth. He worked as a clerk in the Uttar Pradesh Government’s Food Preservation Department for three months just for the kick of it, where his canteen bills exceeded his salary. He extended his hospitality to his office colleagues both at work and after. What he wrote about himself reflects his high degree of self-awareness:

Ghar sé dūr, khāndān sé alag, sarhadoṅ kā duśman, rasmī bandhaṃoṅ sé āzād, dīnī hujroṅ sé nāvāqif, samājī tamāśoṅ sé bézār, siyāsī galiyoṅ sé gurézāṅ, fikrī dāiroṅ sé bétāluq, ghar-āṅgan méiṅ bāzārī ravaiyyoṅ ké phailāv sé paréśān, insānī riśtoṅ kī thandak sé muzmahil, tootṭi-bikharti qadroṅ ké liyé ajnabī, magar apnī āzād marzī sé ubharné vālé chand usūloṅ ka sakhtī se pāband, nāmvar logoṅ ké darmiyān maghrūr-o-mohtāt, bénām chahroṅ kā bétakalluf sāthī, kāghzī notoṅ ké ta’āluq méiṅ fazūl-kharch, magar ārzū karné, rāy banāné, pyār déné aur vafādārī baratné kī rāh méiṅ intihāī bakhīl, kuchh kar guzarné kī salāhiyat se māmūr, magar sāth hī khwāhishoṅ kī duśmani sé bharpūr – bétā banā, nā bhāī, sāthī banā, nā dost; kisī bhī rāij kasautī par pūrā utarné kī salāhiyat sé mahrūm. Ghar, samāj, nasl, qaum, vatan, dīn, zabān, tahzīb, khun, tārīkh – kisī bhī ta’āsub, jazbé yā izm sé phūt ké bahné vālé, lāmbé, khuśrang, khaufnāk daryāoṅ ké thandé, gunguné pāniyoṅ sé bahut dūr, tanhā aur udās, bojhal aur pyāsā!

Away from home, different from the family, a foe of borders, free from all the ritualistic bondages; unbeknownst to the closet of religions; apathetic to the spectacles of the society; escaping the political corridors, indifferent to the bounds of worries, agitated in home, courtyard, at the ever-spreading packaged traditions; exhausted with the coldness of human relationships; a stranger to the crumbling honours; but strictly bound to the few principles that rose with unconventional free-spiritedness out of volition. Known as haughty and cautious amongst the famous; an informal friend to the unknown faces; extravagant with money but stingy when it came to desires, forming opinions, extremely miser while showing love and practicing fidelity; determined to do something momentous; but at the same time, full of animosity towards wishes – neither became a son, nor a broter – a companion – a friend; devoid of any ability to prove purity on the touchstone of prevailing standards. Home, society, progeny, community, nation, religion, language, civility, blood, history – far from all kinds of prejudices and passions and ‘isms’ that sprung forth and flowed as colourful, terrifying, warm waters; solitary and dejected; burdened and parched!

The following words were printed on his visiting/calling card:

Zindagī kī taṛap, uskī thoṛī samajh, shāyirī kī lagan, aur kāfir qalam

A thirst for Life; little bit of understanding, passion for poetry and a deviant pen

They were drawn from a couplet he wrote with extraordinarily long meter:

Zindagī kī taṛap, uskī thoṛī samajh, shāyirī kī lagan, aur kāfir qalam, bas yahī har ghaṛī sāth méré rahé, mahīné baras gungunāté rahé, shér hoté rahé, gīt bunté rahé

Fikr-o-fan ké liyé, zindagī kī khushī, pyār kī ārzū, rūh kī tāzgī, sab lutātā rahā, khud bhikhartā rahā, is tamāśé kī lékin kisé hai khabar, maiṅ nazar méiṅ zamāné kī āyā nahīṅ

A thirst for Life; little bit of understanding, passion for poetry and a deviant pen; only these stayed by my side every moment; months kept humming into years, couplets written, songs composed.

For the sake of thoughts and talent, the bliss of life, the desire for love, the zest of a rejuvenated soul; he generously spent while himself got scattered, but who has witnessed this spectacle? I was not noticed by the world.

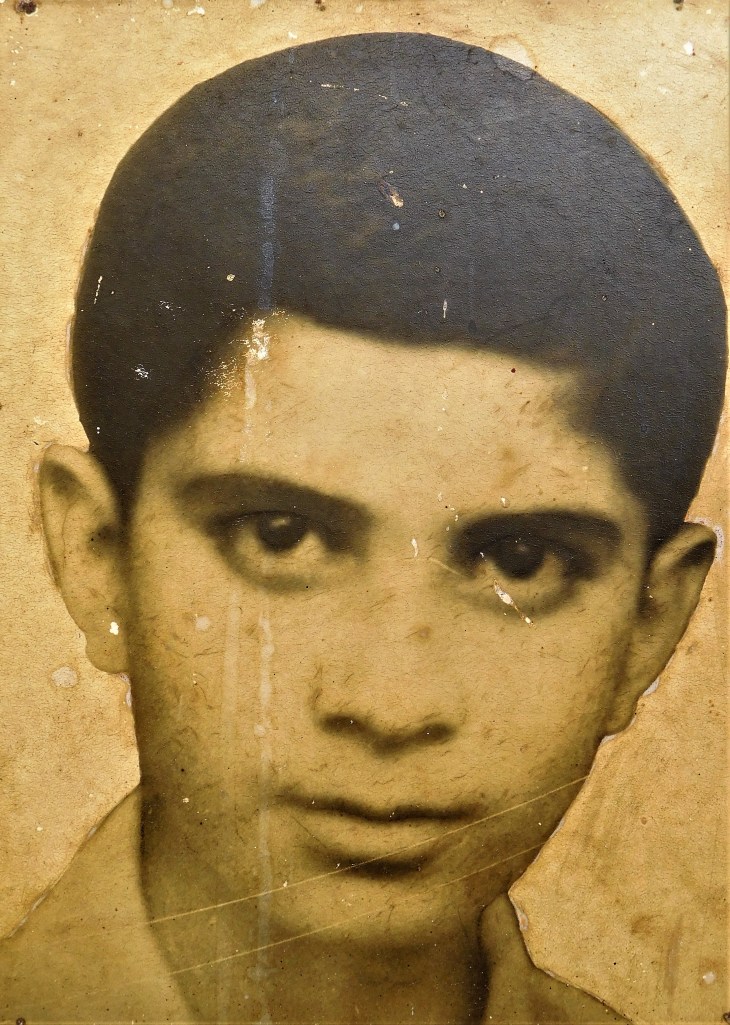

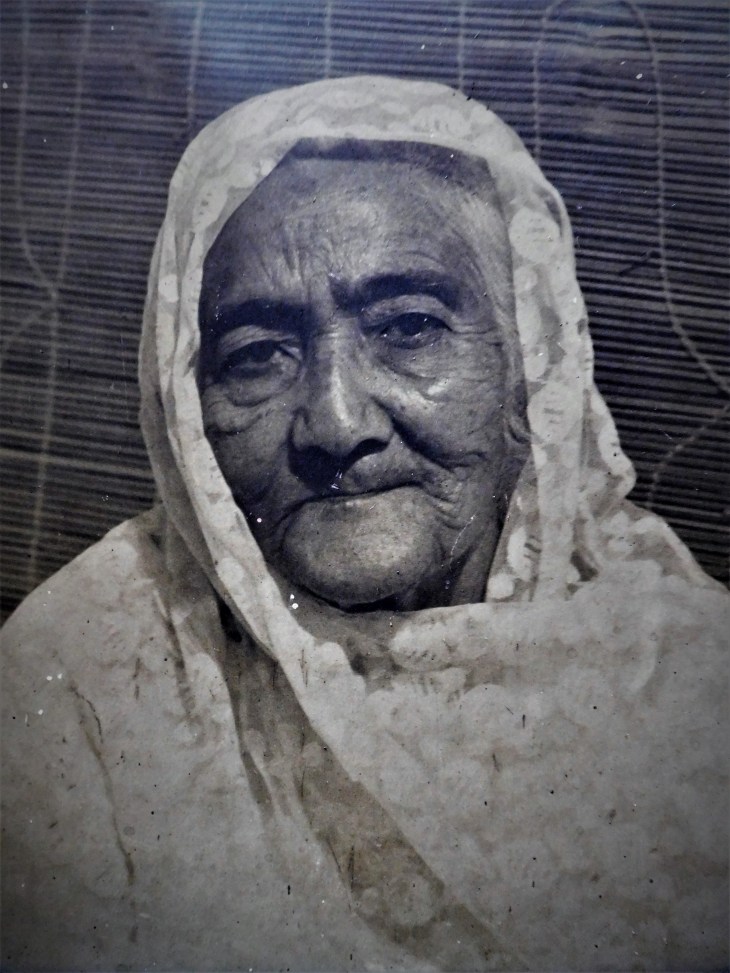

The youngest child of his father Abdul Bārī Khāṅ (1886-1940) (who held the title of ‘Khan Saheb’ conferred upon him by the British for his significant contributions to horticulture), he was named Anwar Kamāl Khāṅ by him upon his birth on 22 October 1937 in Malihabad, District Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh. Abdul Bārī Khāṅ was strongly impressed by the two key figures of modern Turkey, Ismail Enver Pasha (1881-1921) and Mustafa Kemal Pasha (1881-1938), and thus named his two youngest sons after them. I doubt if he was aware that Ismail Enver was one of the principal perpetrators of the Armenian genocide. When my father Anwar reached the tertiary level of education, he added the name of his Pashtūn/Pakhtūn/Pathān (the three terms are used interchangeably and henceforth only Pathan would be used to refer to them) tribe, Aafreedi, to his name. The encyclopaedic spelling is Afridi, yet he spelled it the way he did only to emphasise the long vowels in the name. But it was with the pseudonym Anwar Nadeem that he published. Indifferent to all notions of racial and communal pride, he embraced the word Nadeem (Urdu for ‘friend’) to serve as his last name, dropping all signifiers to his ethnic background, which he explained in the following words in 1994:

Méré pasmanzar méiṅ Malihābād khaṛā hai, usī kī mittī méiṅ mérī nāl gaṛhī hai. Marhūm māṅ-bāp kī kaī puśtéiṅ, zamīn kī chādar oṛh ké vahīṅ so rahī haiṅ. Ghar vāloṅ né mujhé Anwar Kamāl Khāṅ Aafreedi banāyā thā, méiné khud ko Anwar Nadeem kī haisiyat sé péś kiyā. Jis patthar-dil khāndān né méré hāth-pair kāté haiṅ, usī né mujhé mérī rotī farāham kī hai. Lucknow méiṅ mérī zindagī kā yé paitālīsvā sāl hai. Méré andar kā nihāyat mukhlis ādmī, āj bhī sab kā dost hai, sacchā aur kharā, magar śahar-é-adab ké bétamīz, jhūté, muta’āsib logoṅ aur ganvār hāsidoṅ ké darmiyān méiṅ bilkul akélā hūṅ!

In my background lies Malihabad. I’m tethered to its turf with my navel-string. The ancestors of my late parents, lie there asleep, covered with the blanket of its soil. My family had made me Anwar Kamal Khan Aafreedi; I presented myself as Anwar Nadeem. The very same hard-hearted family that had amputated my freedom, has given me bread. This is my 45th year in Lucknow. The very sincere man within me, is still a friend to everyone. Honest and crude; but in this civilised city full of uncivilised, untrue, prejudiced and illiterate envious people, I’m all by myself.

In the last decade of his life, he suffixed the first names of his parents Qaiser, his mother, and Bari, his father, to his name Anwar Nadeem. As a result, he came to have multiple names in official documents, which he explained in the following words:

Ghar ké muhabbat nā’āśnā māhaul né Anwar kah ké pukārā. Pahlī darsgāh né Anwar Kamāl Khāṅ ko bartā. Aur university kī satāh par nām ké ākhir méin Aafreedi kā lāhiqā bhī juṛ gayā. Pachās baras kī qalmī kāvishoṅ ko Anwar Nadeem kī rafāqatéiṅ hāsil rahīṅ. Magar āj, umr ké sattar sāl bhogné ké bād māṅ Qaiser, bāp Barī ké nāmoṅ méiṅ khud ko gum kar déné kī khwāhish bahut téz ho gayī hai.

The cold and unfriendly atmosphere of the house called me Anwar. The first school had Anwar Kamal Khan; and on the surface of the university, the title of Aafreedi was also stuck. The literary endeavours of fifty years got the companionship of Anwar Nadeem. But today, after living 70 long years of this life, a fervent desire, to lose oneself in mother, Qaiser’s and father, Bari’s names is growing ardently.

He came from a literary family that produced a number of eminent sāhib-é-divān (those with published collections of poetry to their credit) Urdu and Farsi (Persian) poets in succession. His grandfather was Abdul Rauf Khan ‘Lutf Malihabadi’ (c.1850-1930), author of Naerang-e-Ḳhayāl; his great-grandfather Muhammad Murtaza Khan ‘Wasl Malihabadi’ (1820-1903), author of Gulśan-é-Wasl (1896), and his mother’s great-grandfather was Nawab Muhammad Ahmad Khan ‘Ahmad’ (1828-1903), author of Maḳhzan-é-Ālam (1860), and her great-great-grandfather was Nawab Faqir Muhammad Khan ‘Goya’ (c. 1805-1850), who happened to be the great Urdu poet Josh Malihabadi’s grandfather. Josh Malihabadi (1898-1982) was Anwar Nadeem’s maternal grandmother’s first cousin.

His ancestors came from the Khyber Agency, one of the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) of Pakistan. The territory originally belonged to Afghanistan but was conquered and annexed to their Indian empire by the British after the Second Anglo-Afghan War (1878-1880). Later it became part of Pakistan by default when the state was carved out of undivided India in 1947. His Afridi Pathan ancestors, who traditionally served as mercenaries, came to India as soldiers in Ahmad Shah Abdali’s army during his five invasions of India between the years 1748 and 1761. They settled in Malihabad, District Lucknow, where they became tāluqdārs and zamīndārs and came to hold the title of nawāb and important positions in the administration and defence forces of the principality of Oudh (Awadh) whose capital was the city of Lucknow. The Pathan settlement in Malihabad dates back to 1202 CE, when the village of Bakhtiarnagar was founded by the invading Muhammad Bakhtiar Khalji. But most of the Pathan population came in about the middle of the seventeenth century, and each migrant Pathan clan secured possession of ten to twelve villages around Malihabad. The latest and the greatest wave of migrant Pathans, comprising mainly Afridis, who fought the Marathas in the Third Battle of Panipat for the Afghan invader Ahmad Shah Abdali, arrived in Malihabad in 1761 CE, and made Mirzaganj their base. Mirzaganj owes its foundation to a Mughal called Mirza Hasan Beg (also known as Mirza Hassu Beg). There are Pathans of other tribes also in Malihabad, viz., Ghilzai (popularly known as Qandhari), Bazad Khel, Amanzai and Bangash. Shyam Benegal’s Junoon (1978) was shot at my paternal grandmother’s maternal ancestral home there, depicted as the palace of the protagonist Javed Khan, played by Shashi Kapoor.

My father commenced his formal education from class six in the Amiruddaula Islamia Inter College in Lucknow, and completed his entire secondary education there. At the time of school admission, his date of birth was incorrectly mentioned as 1 February 1942. His family was so averse to anything Western that with difficulty he wrangled his mother’s permission (he lost his father when he was not even three) to wear shirt and pants instead of a shervani (a long formal jacket, part of the Indo-Persian culture that came to thrive in India under Muslim influence) to school. In this matter, the husband of his elder sister intervened on his behalf. He realised very early in life, perhaps when he was all of ten, that he could not bring himself to have faith in the religion in which he was born, or in fact any religion whatsoever. He later expressed it in a couplet:

Ham mazhab-vazhab kyā janéiṅ, ham log siyāsat kyā samjhéiṅ

Har bāt adhūri hotī hai ummīd ké thékédāroṅ kī

Oblivious to talks of religion, we won’t comprehend politics too

Everything is incomplete of contractors of hope.

The last he offered namāz (Islamic prayer) was when he was coaxed into doing so by a close friend of his, immediately after the release of his high school result, to thank God for enabling him to score the highest in all sections of his class in his school. The only time he ever fasted during the Islamic holy month of Ramzān (Urdu of the Arabic Ramādān) was on the occasion of his rozā kushāī (the first fast of a young believer during the Islamic month of Ramzan/Ramadan). Even that he could not keep in entirety and broke it just a few minutes before the scheduled time when the little child that he was could not stay thirsty anymore after spending an entire day without water during the extremely hot summer of the plains of northern India. Till his last breath he was a non-believer who had a Muslim burial. After this realisation if his remains are exhumed, it would neither bother him, wherever he is, if at all, nor me. His attitude was that of absolute indifference to the fate of his mortal remains:

Maiṅ apné safar méiṅ akélā rahūngā

Mérī fikr kā rāstā hī nayā hai

I’d be alone in my journey,

The way to my imagination is newfound.

My father was enrolled for BA at the University of Lucknow for seventeen years. Not that he failed to pass the examination, it is just that every time he would leave home for the examination he would meet some acquaintance or the other on the way, and out of respect for the person he would drop the examination and instead take the person to a food joint to extend him some hospitality. It was in the seventeenth year that he appeared for the final examination of the three-year-Bachelor’s programme. He did so to satisfy the pre-condition of his graduation by the woman he loved, a Jāt from an Ārya Samājī Hindu family. He gained both a degree and her hand in marriage.

Theirs was a civil marriage. Interestingly, one of their marriage witnesses was Ravindra Agarwal, a member of the Hindu nationalist organisation Rashtriya Swamsevak Sangha (RSS). Today Hindu nationalists have coined the concept of ‘Love Jihad’, a Muslim conspiracy to marry Hindu girls to convert them to Islam to outnumber the majority Hindu population.

Out of deference to my mother who was a vegetarian, my father became a vegetarian. He was so true to his vow of never touching anything non-vegetarian that he would always go hungry at mushāirās (gatherings of Urdu poets) for nothing vegetarian would ever be served. This was no little sacrifice for he had grown up in a family where a vegetarian meal was beyond imagination. My mother and all her five sisters were deprived of non-vegetarian food unlike their four brothers so that they did not take a liking for non-vegetarian food. Their parents, my maternal grandparents, pre-empted that it could be problematic if any of them was married to a vegetarian who did not approve of consumption of non-vegetarian food, as it could then be difficult for the girl to give up her love for meat.

He initially did not give me any surname, but when the school administration insisted on one, he suffixed Jaat (the encyclopaedic spelling is Jat but he spelled it with double ‘a’ only to lay stress on the long vowel), indicative of my maternal lineage, and Aafreedi (his own surname), indicative of my paternal lineage, to my name. But I have now stopped using my middle name at the insistence of some of my maternal relatives, as I felt that I being seen as connected to Hindu Jats at large and to them in particular made them a bit uncomfortable. The martial, warlike Jats are notorious for honour killings and foeticide, particulary in Haryana. Given their intolerance towards intercaste and interfaith marriages of their girls, my maternal family has been exceptionally tolerant. They disguised the real motive by saying that it just sounded too casteist, but I doubt that. My youngest aunt insisted for a number of years after my mother’s marriage that she replace her surname with my father’s pseudonym Nadeem. She did so to the extent that she actually started writing her name as “Manju Nadeem” in the letters that she sent her. She obviously did not want her sister to retain her caste name even after her marriage with a ‘Muslim’ as she saw it. She is the same person who once asked me if Mecca and Medina were in Pakistan! She holds a Master’s degree in Economics! She was also one of the only two daughters of my maternal grandfather among his six daughters to be given primary and secondary education in a school. The elder ones were never sent to any school for there wasn’t any in their village, but all boys were even if they had to be sent hundreds of kilometres away to Lucknow for that purpose. It was only because of sheer determination that my mother could attain tertiary level education and that too up to the doctoral level. This aunt took great offense when I published an autobiographical essay in which I mentioned how a Hindu cousin of mine had once expressed to me the desire to travel back in time so that he could kill Muhammad, under the belief that it would hurt me and it left me wondering why he wished to hurt me. Although I mentioned neither his name nor his location, what revealed his identity to the extended family was the mention that in spite of this strong hatred for Muslims he had no reservation in serving an oil rich Muslim country where he has been happily working for more than a decade. She confronted me instead of expressing any regret or advising her son to do so. Her son immediately unfriended me on Facebook fearing his fate if his identity became known.

I often heard my father say that one of the saddest days of his life was when I, his son, had to be circumcised on medical grounds. I was not even familiar with the term ‘katuā’ (a Hindi pejorative reference to Muslims being circumcised) when I first encountered it at the age of eight or nine. I was a little child when a class fellow used it to address me. I still remember that because of my unfamiliarity with the term I ended up Anglicizing it while narrating the incident to my parents. I asked them the meaning of ‘cut-way’ for that is how it sounded to me when I was addressed with the term ‘katué’ (Hindi/Urdu words that end with the sound ‘ah’ as denoted by the letter ‘a’, often change in a way that the last vowel transforms to sound as ‘é’.). Instead of any word of sympathy I got a reprimand from my Hindu mother as she felt I must have said something provocative.

Years later she came to suspect me of leaning towards Islamic fundamentalism seeing my interest in Islamic tele-evangelical channels. She did not realise that the interest emanated from my scholarly interest in understanding Muslim attitudes towards Jews as betrayed in the Muslim religious discourse. As a little child she made me memorize the gayatri mantra, unlike my father who not only never taught me anything even remotely Islamic in nature but also never even gave me any lessons in Urdu, a language the English medium school I attended did not teach. He feared that if he did, he could be seen by her and her extended family as attempting to mould me, their only child, into his Muslim culture via his language. This decision of his deprived me of the rich family legacy of Urdu literature. My mother has long held the view that a leader from the BJP and a Union Minister, Giriraj Singh, only recently expressed, that all Muslims in India should have been sent to Pakistan when it was created as a state for the Muslims of undivided India in 1947 (Kumar 2020). She considers the Muslims to be eternally grudging and demanding and believes India should have been declared a Hindu State right at the time of partition. She refuses to acknowledge that there is any degree of discrimination against Muslims in India. It was with her in mind that he wrote the couplet:

Vo Hindu hai, mujhé Islam ka bétā samajhti hai

Use acchā nahīṅ lagtā méré akhbār ka paṛhnā

She’s a Hindu, thinks I’m a son of Islam

It unsettles her to see me read the newspaper

But in all fairness, it must be mentioned that my mother was by my father’s side till his last breath and nursed him when he suffered terribly with Parkinson’s during the last two years of his life. She did not leave any stone unturned to prolong his life.

While referring to certain things he would often say that I would understand them when I grew up. What is noteworthy is that he continued to say so long after I was 18 until the time he was not robbed of his ability to speak by Parkinson’s a couple of years before his demise. I have to admit that I did take offense to it then, but now I do not when I realise how my father never visited my maternal relatives, the siblings of my mother and their children. He perhaps knew that his being connected to them through his marriage with my mother could be a source of embarrassment to them in their respective circles because of his Muslim background. This realisation descended upon me only when a number of my maternal relatives, all Hindu, joined Facebook during the last five years and started posting things extremely prejudiced against Muslims. He never saw those posts, but he was wise enough to sense everything.

It reminds me how my father once overheard my mother and her brother, both of them scholars and academics, discussing whom the newsreader presenting the evening-news bulletin resembled. What made it worth taking notice of was the fact that the newsreader was at that moment breaking the news of the demolition of the Babri Mosque earlier that day. My father was appalled by this indifference and apathy shown by them to the extent that he lapsed into silence for several days following that. That same uncle of mine once expressed his annoyance with the fact that Hindu actresses worked opposite Muslim actors in such a large number of Bollywood films. His understanding was that it was so because the Muslim mafia-sponsors liked to watch Muslim men romance Hindu women. Now when I look back I find myself able to connect all the dots. It all makes sense in retrospect. My mother came from an Arya Samaji family. Arya Samajis had been most vehement in their opposition to Muslims and have been one of the most important sources of the ‘Love Jihad’ scare taking us back to the beginnings of Hindu nationalism. Census data was spread to build a threat of a Muslim demographic domination considering their alleged quicker reproduction. It was an Arya Samaji leader Swami Shraddhanand in the first decades of the twentieth century who was most influential in contributing to this stereotype. He repeated the views expressed by U. N. Mukherjee in a series of articles in the Bengalee Journal. Mukherjee claimed that Hindus would disappear after 420 years for the Muslim peasants possessed more stamina and appetite for sex. Thus, Hindus were a dying race, according to Mukherjee. Shraddhanand used Mukherjee’s points to justify Arya Samaj’s actions to proselytize non-Hindu communities (śuddhi) as well as organise and consolidate the Hindu society against the Muslim adversary (Iwanek 2016: 359-360). My maternal great grandfather Kunwar Hukam Singh, Raīs, Angai estate, District Mathura, who served for some time as the President of the All India Arya Pratinidhi Sabha, made his own contribution to it by indulging in caste-engineering by forming a confederacy of certain castes of North India that were seen as warlike. He called the confederacy ‘Ajgar’, which was actually the Hindi acronym अजगर for those castes, viz. Ahir, Jat, Gujar, and Rajput. His son, my maternal grandfather Kunwar Jai Dev Singh once unsuccessfully contested election on a ticket from the Hindu right wing party Jan Sangha, the predecessor of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), for a seat in the Legislative Council. Perhaps decades later my father had become conscious that he had been discourteous to my uncle. To make amends for coldness towards him, my father requested him to write the preface for his forthcoming selection of poems. My uncle, his brother-in-law, readily obliged. An excerpt from that preface is as follows:

The world resounds with the words of religion; with the messages of many messiahs. They inform our understanding of life, and influence and regulate our conduct. But their main precept is love and compassion, and certainly not divisive conflict; universal brotherhood and not sectarian strife. The Rasuls or prophets seek to contain the ocean in a well of their revelations; and every revelation takes us forward to perfection; but the sword is by no means its instrument of dissemination. Hatred, intolerance and violence amount to a travesty of true religion, whatever its name. Rama, Krishna, Buddha, Mahavira, Muhammad and Nanak were all prophets of love, justice and human fraternity. The truth in its entirety cannot be contained in a single revelation. It is dynamic; it evolves; it expands; and the Divine Voice cannot ever fall silent. The messengers of God come to right the wrongs of every age. Anwar Nadeem is most succinct when he asks: “Who is it that comes close to me early in the morning to say, ‘where shall I find the final word, for I speak to every age’.” Truth is the story of our spiritual evolution that knows no bounds and brooks no cessation. We cannot silence the voices that will go on expressing the Truth. Any prohibitions on free, exploratory and constructive speech detract from the scope of our certitude.

Poem entitled “Tauhīn” (Insult) tells us that ‘God is one and Muhammad is his prophet’, which is a message for our hearts! But there are those, alas, who have sought to write it on the sharp edges of their swords which, they do not realize, is an insult to the great Prophet.

In the same vein, poem “Jai Śrī Rām” says: ‘If you come with a sword in hand shouting Śri Rām, I shall not be able to join you and say Jai Śrī Rām. But if you come to me with the pious name of Ram illustrating the values he embodied, come with me, I shall not only be with you, I shall lead you!

In fact “Jai Śri Rām!” came to adorn the front entrance to our house, and “Jai Śri Kṛśṇa!,” the rear entrance. One plaque reads: Imām-é-Hind, Ādarsh Nizāmī, Jai Śri Rām! (The Spiritual Leader of India, Founder of an Ideal Social System, Hail Lord Rama!) and the other, Safīr-é-Shujā’at, Anurāg Payāmī, Jai Śri Kṛśṇa! (Ambassador of Courage, Messenger of Love, Hail Lord Krishna!) In doing so, he, a poet, believed he had reclaimed the Hindu mythological figures of Ram and Krishna from the aggressive Hindu nationalists, who had wrongly appropriated them. Ram and Krishna, in fact, he believed, belong to all Indians as their collective cultural heritage. My father had expressed his awareness of my predicaments due to the constant tensions in a poem:

Yé kaun méré qarīb āyā

Hamāré māzī méiṅ janm lékar vo ék laṛkā javāṅ huā hai

Usé yé gham hai kī usné kaisé ajīb logoṅ méiṅ āṅkh kholī

Koī batāyé kī bāp térā vafā ké naghmé sunā rahā hai

Koī batāyé kī térī māṅ bhī prém nagarī méiṅ gāmzan hai

Koī batāyé kī térī hastī kuchh aisé riśtoṅ ko chū rahī hai

Kī jin sé pahlé milan kī kirnéiṅ fazā ko rauśan na kar sakī thīṅ

Kahāṅ ijāzat milī thī ab tak ki Jāt laṛki kī ārzūéiṅ

Pathān hāthoṅ kā sāth lékar vafā kī rāhéiṅ gulāb kar déiṅ

Kahān Pathānoṅ kī sarzamīṅ sé vafā kā parcham uthā ké niklā

Mahabbatoṅ kā amīn-é-khushtar, latīf jazboṅ kā ék paikar

Kahāṅ salāmat-ravī kī daulat milī hai aisī kahāniyoṅ ko

Kahāṅ qabīlé ké dāyré méiṅ kisī né aisā qarār dékhā

Hamāré māzī méiṅ janm lékar vo ék laṛkā javāṅ huā hai

Usé yé ġham hai kī usné kaisé ajīb logoṅ méiṅ āṅkh kholī

Usé to mālūm hai ki Jātoṅ kī dil kī dhaṛkan méiṅ bāp uskā

Ajīb dilkash maqām lékar, misāl-é-ulfat banā huā hai

Tamām dānishqadoṅ méiṅ uskī azīm māṅ kī misāl ab tak

Jalā rahī hai jidhar bhī dékho, mahabbatoṅ ké chirāgh paiham

Yé kam nahīṅ hai mahabbatoṅ kī azīm daulat kā ék virsā

Kisī kī hastī ko ābrū dé, kisī kī rāhoṅ méiṅ phūl bhar dé

Magar yé chhotī sī bāt ‘Anwar’ samajh kā hissā banégī kaisé?

Hamāré māzī méiṅ janm lékar vo ék laṛkā javāṅ huā hai

Usé yé gham hai kī usné kaisé ajīb logoṅ méiṅ āṅkh kholī

Who is it who just came close to me

Born in our past, that boy has grown up

His pain being that he opened his eyes amidst the strangest people

Someone tell him, that your father sings paens of loyalty

Someone tell him, that your mother too has set foot in the city of love

Someone tell him, that your life is touching a turf of bonds,

That was erstwhile untouched by the rays of union

For who had ever given consent till now that a Jāt girl’s desires,

Would tread the path of love holding Pathān hands?

For when from the lands of Pathāns, a banner of endearment had ever risen so high?

A keeper of happiness, a figure of benevolence

When have such stories of moderation ever been rewarded?

When have the limits of clans ever witnessed such passion?

Born in our past, that boy has grown up

His pain being that he opened his eyes amidst the strangest people

He verily knows that in the heartbeats of the Jāts, his father

Occupies a strange yet interesting place; being an example of love

In temples of knowledge, his mother stands tall as an example of dignity,

Igniting the eternal lamps of love all around

Isn’t it enough that a portion of the great inheritance of love,

Bestows a life with dignity and sprinkles flowers on someone’s path?

But how will this small thing ‘Anwar’ ever be comprehended?

Born in our past, that boy has grown up

His pain being that he opened his eyes amidst the strangest people

Although he studied English Literature as one of his subjects for his BA, the only academic degree he ever earned, he was never comfortable in what he considered to be a foreign language. His linguistic chauvinism resulted in his never attempting to speak in English. He did read the English language daily newspaper The Times of India along with an Urdu daily newspaper all his life. When we hosted a British scholar of the Old Testament he stubbornly talked with her in Urdu while I played the interpreter. He loved Urdu and found its Arabicization and Persianization objectionable:

Urdu né Sanskrit ké vatan méiṅ āṅkh kholī, phir bhī Sanskrit kyā, désī/ilāqāi zabānoṅ/boliyoṅ kā koī ék lafz apné makhsūs nukīlépan ké sāth dikhāī nahīṅ détā. Mérī nazar méiṅ yahī ravaiyā Urdū culture kī mubārak buniyād rakhtā hai. Magar afsos ki yahī ravaiyā arabī, fārsī ké āgé giṛgiṛane lagtā hai aur ham urdū méiṅ arabī bolné lagté haiṅ. Hamārī samā’at, hamārī tahrīr, hamārā qalam arbī alfāz ké nukīlépan sé kab tak zakhmī hoté rahéṅgé.

Urdu opened its eyes in the land of Sanskrit. But not just Sanskrit, any one word from any language or dialect, is never seen with its particular sharpness. In my view, these associations lay the blessed foundation of Urdu culture. But sadly, these associations start imploring in front of Arabic and Persian and thus we start speaking in Arabic while talking in Urdu. Till how long our hearing? Our script? Our pen be stabbed with the sharpenss and crudity of the Arabic word.

He also wrote:

Yé bāt acchī tarāh samajh lī jāyé ki Urdū, Fārsī harfoṅ ki zabān nahīṅ hai. Urdū duniyā, khāskar hindostān kī Urdū duniyā, arabi aur īranī tahzīboṅ kī colony nahīṅ hai. Urdū adab, islāmī zikr-o-talīm kī kahārī ké liyé makhsūs nahīṅ hai. Āj kī urdū shāyirī apné mauzuāt ké liyé ghair-mulkī markazoṅ kī taraf nahīṅ dékhtī.

This should be clearly understood that Urdu, is not a language of the Persian alphabet. The world of Urdu, particularly Hindustan’s ‘world’ of Urdu, is not a colony of Arabic or Iranian civilizations. Urdu literature, is not meant to carry Islamic teachings and education. Today’s Urdu poetry doesn’t look towards centres of other countries for want of subjects.

Conscious of the fact that he had lost his father when he was not even three, my paternal grandmother, indulged him. He led an indulgent life – from twenty to forty he spent all his evenings at the cinema with an entourage of friends who were his guests. For the next twenty years, he spent his evenings at Anwar Tea Stall in Aminabad, Lucknow, treating his admiring friends as he regaled them with poetry and prose. He had his ancestral wealth to lean on, while my mother struggled to make ends meet as a tertiary level academic. She shouldered all household responsibilities without any financial help or even any non-monetary cooperation from him. He justified himself unsuccessfully in the following words:

Mainé apné vālid ko apnī jismānī āṅkh sé nahīṅ dékhā, lékin apné baṛe bhāī ko jo mujhsé bāīs sāl baṛé thé, yānī bāp ké barābar thé aur Malihābad méiṅ vakālat kar rahé thé aur zamīṅdārī chalā rahé thé… Lékin unkī zamiṅdārī kuchh is tarāh chal rahī thī ki vo apné kāshtkāroṅ ko bulāté thé, insāf karté thé, aur insāf ké taqāzé is tarāh sé pūré hoté thé ki vo kāshtkār zaḳhmī ho jāté thé. Aur phir ghar sé haldī aur chūna vaghairāh unké liyé jātā thā aur isétmāl hotā thā. Mujhé vahāṅ sé zamīṅdārī ké liyé shadīd nafrat paidā huī. Uské natījé méiṅ mainé vahāṅ kī zindagī méiṅ ék bahaut baṛī jaydād apnī bhūīṅ bhūīṅ kar ké phaiṅk dī. Yānī maiṅ nahīṅ chāhtā thā ki zamīṅdar ban ké rahūṅ.

I didn’t see my father with my physical eyes, but I saw my elder brother, who was twenty-two years elder to me; which means that he was like my father only; and was practicing law in Malihabad and looking after the Zamindari too. But the way his Zamindari was operating was such that he used to call his farmers; do ‘justice’ to them. And justice was served in a way that the farmers used to get hurt. And then from the household, ointments made from turmeric and limestone would go for their usage. It was then when I developed a fervid abhorrence towards Zamindari. As a result, in my life over there, I let go off huge ancestral property by throwing it away despisingly. It meant that I didn’t want to live like a Zamindar.

During his youth, when he was active in theatre, he became particularly notorious for not turning up for the final show in spite of having religiously taken part in all the rehearsals. The only time when he did make an appearance in a final show was when he played Charudatta, the male lead, in the eponymous play Vasantsénā, based on Shūdraka’s ten act Sanskrit drama Mrichkatikam (The Little Clay Cart) (5th century CE). What kept him from slipping away was the fear of losing the goodwill of his ladylove, who played Vasaṃtsénā, the female lead in it. She was also the producer of the play under the auspices of the theatrical society Natarāj Raṃgshālā that she had founded. She later became my mother.

Though he dreamed of acting in films, but made no efforts to realise his dreams. He declined his elder sister’s offer to introduce him to someone in the industry. In spite of the generous offer made by her, he felt she did not approve of his ways. As he was respectful of his sister who lived in Bombay, he never went there to pursue a film career. He thought it may hurt her for he would have not got in touch with her. But an opportunity to act in films knocked twice at his door. First when he was cast as the male lead in a film whose story, screenplay, dialogue and lyrics were all written by him. Somebody else replaced him later to play the male lead. This sudden change was determined by the fact that the replacement or someone related to the replacement was sponsoring the project. The film, however, could never be released. He wrote about his love for cinema in the following words:

Gullī-daṃdā chhūā nahīṅ kanché khélé nahīṅ, cricket yā hockey méiṅ dilchaspī lī nahīṅ, football yā kabaddī kī taraf lapkā nahīṅ, tairākī yā ghuṛsavārī ké pīchhé dauṛā nahiṅ, tāś yā carom né jī ko lubhāyā nahīṅ. Dilchaspī thī film sé. Dil āj bhī usī kī taraf jhuktā hai, badan méin adākārī kī salāhiyatéiṅ réngṭī haiṅ, dil shāyirī ké liyé machalṭā hai, damāgh kahāniyāṅ buntā hai. Magar Sāhab! Yé adākārī kā jauhar, yé shāyirī kī daulaṭ, yé kahāniyoṅ kī fasléiṅ – inkī nikās kā koī tarīqā? Man ki tahdāriyāṅ nā hāṅk lagāné déiṅ, nā ghar sé bāhar nikalné déiṅ. Chahroṅ ké hujūm méiṅ kisī sé riśtā, kisī sé qurbat, magar sab ké āgé bélāg, bélaus bātein aur qahqahé – nā kām kī fikr, nā śohrat kī bhūk, nā daulat kī havas. Zarūratéiṅ pūrī ho gaīṅ to thīk, nā pūrī ho sakīṅ to béparvāh, pūri zindagi nā kisī naśé kā sahārā milā, nā khud sādgī kā dāman pakṛā. Magar Ghalib ké is śér sé jo riśtā thā vo haméśa qāyam rahā:

āvārgī sé go rahé rusvā-é-dahar ham

Bāre tabiyatoṅ ké to chālāk ho ga’é

I never touched the Gulli-danda, nor played with marbles, never took interest in cricket or hockey, didn’t leap towards football or kabaddi; didn’t run after swimming or horseriding; cards and carom didn’t impress me. My interest lay in films. Even today, my heart is inclined towards them. The ability to act crawls through the entire body, the heart becomes anxios for poetry and the mind weaves stories. But gentlemen! Is there a way to channelize the talent of acting, the fortune of poetry and this crop of stories? The layers of the mind don’t allow to shout out or to step outside the house. In this multitude of faces, relations with a few, friendliness with others, but still very different from everyone. Conversation without pretence and hearty laughters – neither worrying about work nor hungry for fame, nor lusting for money. If essential needs were met, then fine, if not, then didn’t care a dime. All my life, I didn’t seek solace in any kind of intoxication nor clinged to simplicity; but the relationship I’d struch with this couplet of Ghalib, remained forever:

āvārgī sé go rahé rusvā-é-dahar ham

Bāre tabiyatoṅ ké to chālāk ho ga’é

Decades later he was roped in by the veteran filmmaker J. P. Dutta to play Urdu’s first novelist Mirza Hadi Ruswa in the eponymous film Umrao Jaan (2006) based on Ruswa’s novel of the same name. Unlike the former, this film was screened, and that too not just in India but in many other countries as well, though it failed at the box office. In spite of his over dramatic performance, he was roped in by drama-director Ashraf Husain to play a prominent character in a television drama series Khwāb Rau, because Husain perhaps felt having somebody who had acted in a Bollywood film would help attract more viewers. Broadcast on the state-owned channel Doordarshan, it was based on Joginder Paul’s Urdu novel of the same title. Anwar Nadeem tells us:

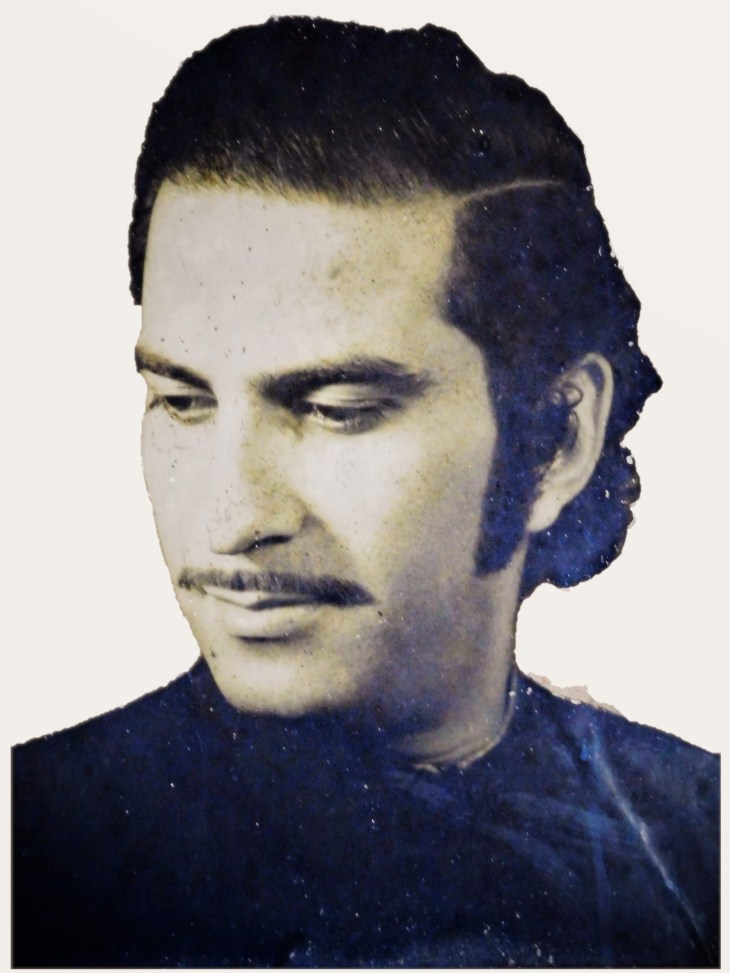

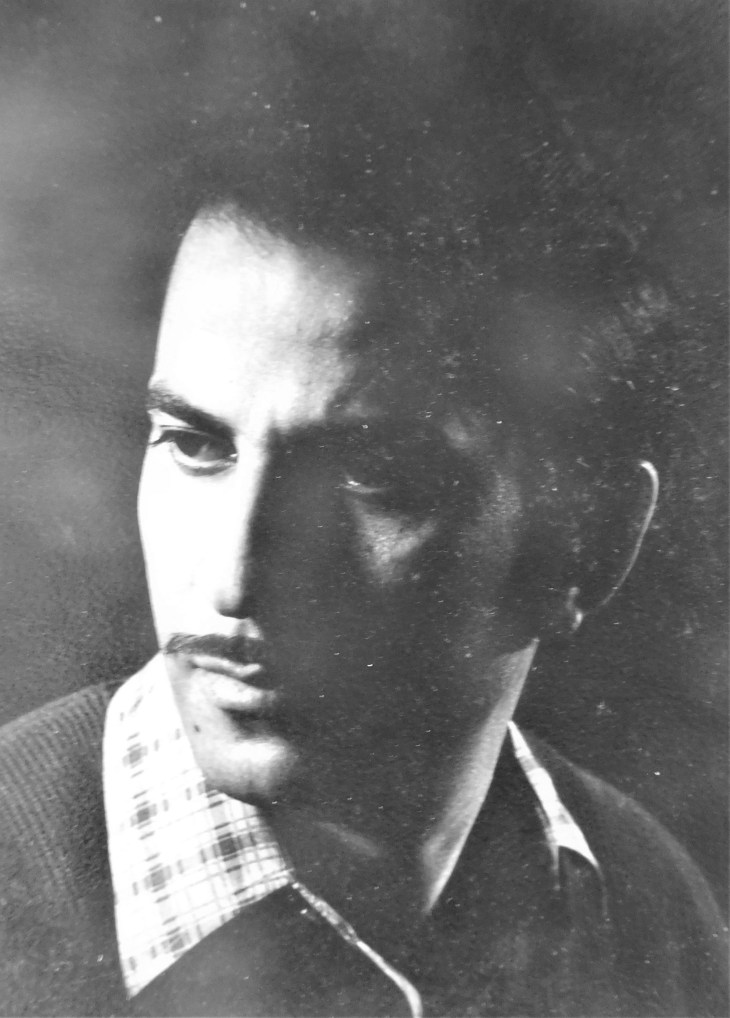

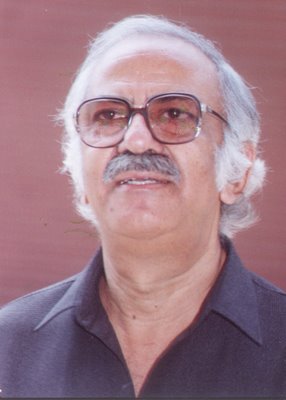

Khud ko filmoṅ sé joṛné kā sapnā Nadeem né das baras kī umr méiṅ dékhā thā aur chaubīs baras bād, Hyderabad ké ék filmmaker kī farmāīś par, yahīṅ Lucknow méiṅ baith kar ék original kahānī likhī thī, jiskā manzar-nāmā, mukālmé aur gīt sab kuchh apnā thā. Gītoṅ ko śohrat milī thī. Film kā ék gīt Mohammad Rafi né gāyā thā aur yahīṅ Lucknow méiṅ Nadeem apnī umr ké chauntīsvé sāl méiṅ pahlī bār kaimré (Camera) ké sāmné āyā thā. San 72 méiṅ sar par kālé ghané sundar bāl thé aur mūṅh méiṅ sundar khūbsūrat dātoṅ ké motī – aur chauṃtīs baras bād 6 April, 2006 ko apné ābāī vatan Malihābad méiṅ Nadeem apnī umr ké chhiyāsatvé sāl méiṅ, āp chāhéiṅ to asl umr ko certificate age ké léhāz sé sirf chausath baras hī samajh léiṅ. Kaimré (Camera) ké sāmné is śakl méiṅ ā rahā hai kī sar pé dūr tak ganjépan kī hukūmat hai aur assī fīsad bāl bilkul saféd haiṅ, baṛī-baṛī āṅkhoṅ par chaśmā birājmān hai aur khūbsūrat battīsī kī kaī dīvāréiṅ toot chukī haiṅ, halāṅkī badan méiṅ kasbal hai, kaléjé méiṅ zor aur āvāz méiṅ jazboṅ kī garmī hai. Nadeem qalam kā dhanī hai aur bahut kuchh likh chukā hai aur abhī kuchh aur likhné kā junūn hai.

Nadeem had dreamt of associating with films from the tender age of ten years and twenty-four years later, on the request of a filmmaker from Hyderabad, an original script was written here in Lucknow itself. The screenplay, dialogues, lyrics and everything was penned by me. The songs had become quite popular. One song was sung by Mohammad Rafi and here in Lucknow, in the thirty-fourth year of his life, for the first time, I faced the camera. In ’72, there was a crop of dense and beautiful hair and the mouth revealed a set of beautiful pearl-like teeth – and after thirty four years, on 6th April, 2006, in his native town of Malihabad, in the 66th year of his life (if you wish you can take my age to be 64 according to the certificate), Nadeem is facing the camera with a profile that reveals the dominion of baldness for quite an area on the head; eighty per cent of hair have greyed, a pair of specs rests on a pair of big eyes, and many walls, of the beautiful set of 32, are now broken. However, there’s vigour in the body; a spirited bosom and a voice that exudes the fire of passion. Nadeem is blessed with a rich pen and has written voluminously while there’s still an intense desire to write more.

He also made a foray in Urdu journalism by singlehandedly bringing out a high quality Urdu literary journal, Adabi Chaupāl, but could not follow-up its inaugural issue with another. What brought an end to the journal, which proved to be a one issue wonder, was the fact that he also took upon himself the task of marketing and distributing it. He adopted a strange way of selling it. He sent it by post to all the prominent Urdu figures of the time by Value Payable Post (VPP), which they refused to accept. All the parcels were returned and he had to bear this expense as well. Decades later he got the opportunity to display his journalistic talent when he turned into the de facto editor of the Urdu literary journal Imkān, whose founder and de jure editor was the popular Urdu poet Professor Malikzada Manzoor Ahmad. He firmly refused to take credit for his services to the journal during its initial years. He continued his work on the journal for as long as his rapidly deteriorating health permitted.

He fancied himself as a publisher and called his publishing house Hamlog Publishers, but the publishing house only published his own books with just one exception. Clearly, he was incapable of making this a profitable venture.

It was his utter disdain for lobbying in his favour, his brutal and unsparing criticism of others and at the same time his refusal to be judged by them, that proved to be the greatest impediments to his ambition, that of recognition. The ambition never turned into an aspiration. V. S. Naipaul famously said that a writer who does not generate hostility is dead. As far as Nadeem is concerned, he generated it in abundance, though he was, certainly not a provocateur as Naipaul was. But he certainly was highly opinionated and very outspoken and cruel in his criticism, which was enough to disgruntle people. As a result, he was completely marginalised. But more than that it was a self-imposed isolation, but definitely not hibernation. He was fully awake and very alert to the latest developments in Urdu literature, but he would only seldom submit anything for publication in any journal, which he explains in this couplet:

Maiṅ inquilāb kī manzil jīt bhi létā

Méré mizāj kī bil’lī né rāstā kātā

I would have conquered the destination of Revolution,

The cat crossed the path of my temperament.

We get an insight into his philosophical approach to life in his nazm “Sīdhī sī Bāt”:

Har ék śahar ko nafrat hai ibn-é-ādam sé

Har ék maqām pé mélā hai talkh-kāmī kā

Har ék ahad méin sūlī uthāyé phirté haiṅ

Vo chand log jo duniyā sé dūr hoté hain

Vo chand log jo thokar pé mār dété hain

Kūlāh-o-takht-o-siyāsat kī azmatéin sārī

Zamīṅ unhīṅ ko payām-é-hayāt détī hai

Vahī payām jisé tum ajal samajhté ho

Every city despises the children of Adam,

Every place has a fair of bitterness,

Carrying the cross and roaming about in each era,

Those few people who are distant from this world,

Those few people who spurn at

The glory of crown, throne, political power,

The earth chooses them to give the message of Life,

The message that you understand as death.

In an interview he gave to Dr. Tariq Qamar, broadcast from Lucknow under the auspices of the Urdu language programme on All India Radio just a few years before his death, he made the contradictory statement, “Qatai taur pé main ék hārā huā ādmī hūṅ, magar mujhé iskā éhsās nahīṅ hai” (I am definitely a loser, but I am not conscious of it).

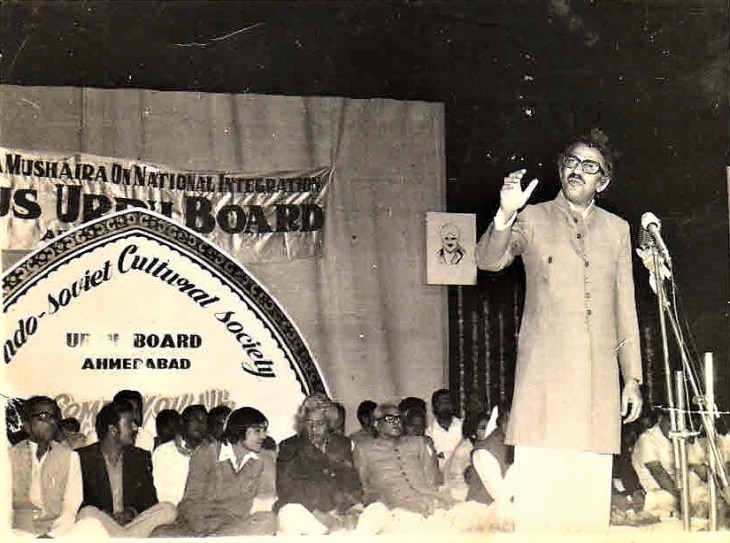

He travelled internationally in a cycle rickshaw when he crossed the India-Nepal border to recite his poetry at a mushaira in Nepalganj, the only foreign trip he ever made. When Dr. Qamar enquired why he stopped presenting at mushairas, he replied, “I kept participating in mushairas with the intention of highlighting the weak points of those considered stalwarts. Urdu speakers never talk of the weaker aspects of their literary giants. I wanted to do so not to refute their greatness but only to emphasize that they were great in spite of the flaws I pointed out.” This is all he said and left the rest for people to understand that this was an approach not appreciated by the mushaira organizers, who stopped inviting him. His collection of mushaira reportages Jalté Tavé kī Muskurāhat (1985) won him awards from the Urdu academies of Bihar and Uttar Pradesh. It is said that the popular Urdu poet Dr. Rahat Indori benefitted immensely from the book during his doctoral research.

There were two strange things that happened on his death. One, that he got a Muslim funeral in spite of not being one. The other was that in all the tributes paid to him the focus was on his hospitable nature with hardly any mention of his literary contributions. The literary dimension of his personality was almost completely overlooked. Urdu litterateurs paid him back by being silent about his literary contributions, not because those did not deserve attention, but because of their prejudice against him. He commenced his poetic journey early in life. It was at the age of 19 that he recited the following couplet at a college event:

Main abhī-abhī ka charagh hūṅ, main zarā méin bujh to nā jāuṅgā

Méré sāth tum to chalé chalo, tumhéiṅ manziloṅ sé milāuṅgā

I’m the lamp of today, won’t extinguish like that,

Come along with me, I’ll make you meet the destinations.

It was one of his earliest couplets. He published several collections of poetry: Safarnāmā (1974), Jai Śri Rām (Collection of nazms) (1992), which he also brought out in the Devanagari script, Maidān (Collection of ghazals) (1994), released in the Devanagari script in 1995 under the title Pānī, and Yé Kaun Méré Qarīb Āyā (collection of selected poems) (2014). He also published a collection of his essays, Muhab’bat Kārfarmā Hai (Collection of essays, 2012), and the film script he had written, Kirchéiṅ (Urdu in the Devanagari script) (2013). He was never a member of any literary organisation or part of any movement. He resisted all labels, but the influence of the Progressive Writers Movement, which had its first conference in 1936 in Lucknow, a year before his birth, is palpable in his poetry:

Tum né yé sach kahā méré śéroṅ méiṅ ab zindagī ké tamāśoṅ kī bātéiṅ nahīṅ

Kuchh masāil kī jānib iśārāt haiṅ, kuchh khayālāt hain, kuchh bayānāt haiṅ.

You’re right, my poetry no more talks about Life’s spectacles,

There are some hints at issues, some thoughts, some statements.

The only influence on him that he acknowledged was that of his second eldest brother, twenty years older than him, Wali Kamal Khan, who wrote prose and poetry with the pseudonym Arif. Wali Kamal Khan was a strange character who renounced the worldly comforts and luxuries that he enjoyed as a scion of a feudal family and embraced the life of a Hindu ascetic when he joined the Radha Soami Hindu sect. But left it for Bahaism when he could not find the spiritual solace he was in search of. He devoted himself to the proselytization of Bahaism for eight years until he converted to Christinanity. His faith was actually a syncretism of different religions. Anwar Nadeem once said, “Āj jo kuchh bhī maiṅ hūṅ, mérī soch ké jitné dhāré haiṅ, vo sab Walī Kamāl Khāṅ ‘Arif’ ke zéré asar haiṅ.” (“I owe all that I am today, all strands of my thought, to Wali Kamal Khan”.)

In spite of all biases against him, even those who ignored his literary contributions could not keep themselves from showering praises on him for his hospitality in the tributes they paid to him upon his demise. He was not without eccentricities. He did not see his two eldest brothers, including Wali Kamal Khan, the one who strongly influenced him, for more than two decades despite their being no conflict between them. He never tried to learn how to drive. He rode a scooter, but never bothered to change the gear. Always rode it in the same gear, irrespective of ascent and descent and no matter what the speed. Continued to do so until advised one day to never ride a two-wheeler because of the hernia he had developed. He accepted the advice but refused to get himself operated. Years later, he had to undergo the required surgery in an emergency. When my mother purchased a second hand car, he refused to get in it even when both of them had the same destination. He would instead take public transport. This continued until she bought a brand new car in which he agreed to share rides with her. He never made any phone calls all his life, though he was not averse to taking calls on landline. He never held a mobile phone.

It was at dawn on 9 August 2017 within minutes of having received the news of my father’s demise that I got a call from my Hindu maternal uncle settled abroad. He not only paid condolence but also insisted that I must ensure that his last rites are performed exactly according to the tradition in his family. I did not have to do anything in this regard, for by the time I managed to reach Lucknow from Kolkata my paternal relatives, Muslim neighbours and friends had already made all arrangements. I just went with the flow in a spirit of deference to them. Within a day or two of my apostate father’s Islamic funeral I found myself at a neighbour’s door begging for ice for my youngest maternal uncle (not the one mentioned above), a retired professor, who had come from another city to pay his condolences to us and to stay with us for a few days. Our freezer had malfunctioned but the uncle just could not do without his evening peg, even at a time of mourning.

Anwar Nadeem is a poet still waiting to be discovered. Many of his works can be accessed online, at the website of Rekhta. He had written:

Kuchh logoṅ kā khayāl hai

Samāj né mujhé apné se alag kar diyā hai

Kuchh log samajhté haiṅ

Maiṅ apné samāj se kat ké rah gayā hūṅ

Méré bāré méiṅ āp yahī yād rakhéiṅ

Maiṅ haméśā likhtā rahā hūṅ aur sochtā rahā hūṅ

Mumkin hai mérā qalam, mérī shāyarī

Kabhī méré samāj, mérī duniyā ké kām āé.

Some people think

Society pushed me aside from the mainstream

Some people think

I’m cut off from the society

Remember only this about me,

I’ve always been writing and reflecting,

May be some day, my pen, my poetry,

Is of use for my society, my world.

He never got the recognition he richly deserved, but who knows what he prophesied may come true in the future:

Maut ke sāth janm légī hamārī śauhrat

Log is śahr sé pūchhaiṅgé hamārā kamrā.

Our fame would be born with our death,

People would inquire this city about our room.

References

Datta, Pradip Kumar, “‘Dying Hindus’: Production of Hindu Communal Sense in Early 20th Century Bengal”, Economic & Political Weekly, June 19, 1993, Vol. 28, No. 25, 1305-1319. Accessed on October 21, 2020 at https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/4399871.pdf?refreqid=excelsior%3A3acefa2b43778535a47fab8b5b56c807

Iwanek, Krzysztof, “‘Love Jihad’ and the stereotypes of Muslims in Hindu nationalism”, Journal of Alternative Perspectives in the Social Sciences (2016) Volume 7 No 3, 355-399.

Kumar, Madan, “Muslims should have been sent to Pakistan in 1947, says Giriraj Singh”, February 21, 2020. Accessed on June 9, 2020 at https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/muslims-should-have-been-sent-to-pakistan-in-1947-says-giriraj-singh/articleshow/74249011.cms

Nadeem, Anwar, Jai Śri Rām (Lucknow: Hamlog Publishers, 1993) (Urdu in the Devanagari script)

- Pānī (Lucknow: Hamlog Publishers, 1995) (Urdu in the Devangari script)

- Kirchéiṅ (Lucknow: Hamlog Publishers, 2007) (Urdu in the Devanagari script)

- Yé Kaun Méré Qarīb Āyā (Lucknow: Hamlog Publishers, 2007) (Urdu in the Devanagari script)

Bio:

All translations from Urdu are by Saira Mujtaba except mentioned otherwise. She is an English news anchor with the All India Radio and a freelance journalist and translator who has published in a number of leading periodicals in India.

The author, Navras J. Aafreedi, is an Assistant Professor in the Department of History, Presidency University, Kolkata. He is most grateful to his friends Professor Heinz Werner Wessler and Dr. Jael Silliman for reading the initial draft of this essay and for helping him improvise it. He is deeply indebted to his friend Saira Mujtaba for all the translations.

***

Like Cafe Dissensus on Facebook. Follow Cafe Dissensus on Twitter.

Cafe Dissensus Everyday is the blog of Cafe Dissensus magazine, born in New York City and currently based in India. All materials on the site are protected under Creative Commons License.

***

Read the latest issue of Cafe Dissensus Magazine, “Shaheen Bagh and the Anti-CAA Protests: The Struggle to Create New Concepts”, edited by Huzaifa Omair Siddiqi, JNU, New Delhi, India.

Awesome blog post. I Like it.

Please check out my blog & share your thoughts about it.

https://rajblog5.com/2020/10/20/famous-festival-of-navaratri-in-india/

LikeLiked by 1 person